Remarks on Receipt of the Chief Academic Officers Award from the Council of Independent Colleges

November 1, 2008

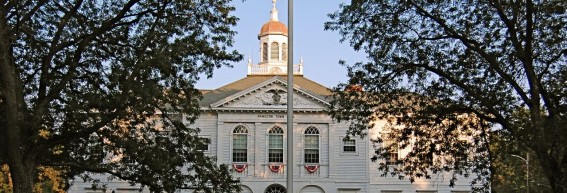

Like many of you, I have already voted. Four days ago I walked into the town hall in my hometown of Hamilton, Massachusetts, and filled out an absentee ballot. Voting in the town hall is a ritual that I now associate with the CIC conference, since our events here usually stretch over onto Election Tuesday, and that requires some advance action.

Now, by New England standards, Hamilton is a brash young suburb. Compared to all of the Puritan settlements nearby, our town was founded just yesterday—well, that is in 1793, not long after the nation adopted the Bill of Rights. In the center of the town seal is the profile of one of the strongest opponents of that Bill of Rights: 32-year-old Alexander Hamilton.

Actually, I love voting in the Hamilton town hall. Walking into the old Federalist building, with its Georgian portico and creaky floorboards, makes me feel closer to those early, nervous days of American independence. And every four years the blend of the Federalist town hall, the national election, and the CIC conference prompts me to think about how a gathering of independent colleges matters to democracy.

Our village namesake Mr. Hamilton, though, might have been a bit skeptical about the alliance of so many independents, whether they were colleges, states or whiskey rebels. Consider this warning from The Federalist Papers: “To look for a continuation of harmony between a number of independent, unconnected sovereignties . . . would be to disregard the uniform course of human events, and to set at defiance the accumulated experience of the ages.”

I can’t speak for the ages, but I do know that in my experience over the past fifteen years I have greatly appreciated the harmony that has continued among my independent colleagues. But I hope it is not simply a peaceful co-existence. Independent colleges do get praised for providing students a panorama of free choices. But we need more than freedom. Increasingly, I am convinced that one of the real tests of leadership for chief academic officers is whether we can use our independence to harvest our diversity. Whether we can learn from the courage of each other's purposes.

At its best, this conference has helped me see educational trends, global issues, and federalist mandates—even the best ones, like those related to access and accountability—through the lenses of our distinctive missions. Missions to serve a unique, often underrepresented population. Missions drawn from the vitality of our religious traditions. Missions built upon creative strategies for civic engagement. Missions that transcend mere compliance or standards and develop new ways to educate for social hope.

There are so many people in this room that I should thank for their encouragement and support, but let me mention one person who is not here—my father. These are the kind of moments that one would like to share with one’s father, but, sadly, in the past months his memory has failed him. A life-long teacher and administrator, my father, Joe, was also a pretty good plumber. And a great ceramic tile installer, an educator as well as a craftsman. He was always anxious that I season my love of the liberal arts with some blue-collar savvy. That I remember that educational leadership is often about fixing things, whether they are rusty pipes in the dorm, rusty general education programs, or broken human relations between faculty members. Indeed, in our small college contexts, where CAO’s cover such varied terrain, so much of what we do in our roles is fix things that we often get pushed to learn new skills. When young, I once asked dad how he learned so many trade skills, and he said that he got them up by trial-and-error and by eavesdropping. Admittedly, I have done my share of trial-and-error on my own campus. That’s one reason, perhaps, why I need to come back here to eavesdrop on so many good minds and new ideas at CIC.

Certainly that listening has led to gaining some new tools of the trade—such as tools related to measuring faculty loads or leveraging financial aid. But, even more compellingly, I have also listened in on conversations about students and NGO’s in Sierra Leone. And about a “Great Books” curriculum that blends the study of classics with literacy tutoring in local public schools. And about social work and engineering classes that went to Louisiana in the aftermath of the hurricane. And I come away thinking that our contribution to democracy has less to do with producing graduates than with new strategies for awakening the moral imagination of our students.

So thank you for letting me listen in for the last fifteen years. You have probably heard it said that awards only have as much value as the quality of the people and organizations that grant them. In that light, be assured that I am honored to receive this one.

(Top photo: Hamilton Town Hall)

Essays about Gordon

Essays about Gordon