STILLPOINT Archive: last updated 12/12/2012

By Jennifer Hevelone-Harper

“We followed the experiences of early Christian monks who sought out a life of fasting and prayer in the remote region where God appeared to Moses.”

One of my teaching assignments as a grad student at Princeton was for a study-abroad program in Wadi Natrun, Egypt. In this cradle of historic Christian monasticism, in the desert halfway between Cairo and Alexandria, I had the privilege of teaching the History of Early Christianity to undergraduate Americans, including two students of Coptic (Egyptian Christian) ancestry.

Our program was housed in one of five ancient monasteries in the wadi. Four were still active and vibrant, in the midst of a spiritual renewal movement that had sent hundreds of Coptic men with degrees in engineering, law, and medicine to take formal vows of poverty and obedience in desert monasteries. Each Sunday we joined the monks and hundreds of pilgrims from Cairo for worship in the monastery church. We worked at an archaeological excavation of the one monastery no longer flourishing, the Monastery of John the Little, abandoned in the fourteenth century.

An ancient prayer

As we uncovered sand from fourth-century monastic cells, we found the ancient Jesus Prayer inscribed in Coptic on a wall: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the Living God, have mercy on me a sinner.” The echo of modern and ancient prayers of Egyptians profoundly drew me into a part of the living global church that I had previously known only from dusty library volumes.

One of the pivotal experiences of the semester was visiting St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mt. Sinai. In a rickety mini-bus that seemed to leak noxious fumes into the passenger cabin, we crept at a grueling 35 mph out of Cairo, and east through government checkpoints in the Sinai Peninsula to this Byzantine fortress built where sixth-century Christians believed that the Lord had spoken to Moses out of a burning bush.

Inside the cloister walls

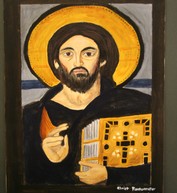

As we entered through the meters-thick monastery walls and were ushered into the dim chapel, our breaths were taken away by a glimpse of the glittering golden mosaic of Christ’s transfiguration in the apse of the chapel. We joined the prostrate disciples depicted below the divinely radiant Christ and the prophets Moses and Elijah, in their attitude of awe and reverence. We saw sixth-century icons of Christ Pantocrator (Ruler of All), the Virgin Mary, and the gray-haired Apostle Peter clutching the keys to the kingdom of heaven. These icons are the earliest surviving panel paintings in Christian tradition, preserved in the remote reaches of Sinai from both marauding Bedouin and imperial iconoclasts. We knew better than to ask to see the monastery’s library, home to many historically significant volumes, since the monks, having been pillaged by colonial scholars, are wary of showing their real treasure to western visitors.

A return journey

This past year I have been privileged to return to Mt. Sinai with students—not via planes and buses, but in courses taught in the History Department. Last fall I taught an advanced seminar, Mt. Sinai in Early Christian Tradition. After reading through most of the Pentateuch, students read primary sources composed on Mt. Sinai through the seventh century. We followed the experiences of early Christian monks who sought out a life of fasting and prayer in the remote region where God had appeared to Moses. The monks' trials at the hands of pagan Bedouin and Muslim conquerors kept my students enthralled.

In another course, Special Topics: Introduction to Syriac Language and Literature (co-taught with my colleague Dr. Ute Possekel), students studied eastern Christianity and Syriac, a dialect of the Aramaic language Jesus spoke. Syriac was widely used in the Middle East by Christians from the fourth-century onwards, and even today it is the liturgical language of several middle eastern churches. The class worshipped with a diaspora community in West Roxbury, and the students were thrilled to be able to follow along in a Syriac prayer book.

Next steps

This journey into Syriac Christianity at Mt. Sinai will continue next semester. During my sabbatical I will be working with Dr. Possekel and students who have studied Syriac to translate an ancient manuscript from Mt. Sinai, the Codex Climaci Rescriptus. This project is sponsored by the Green Scholars’ Initiative, an institution which supports teacher-mentors working on research with undergraduates. They have provided us with high-resolution digital images of the ancient manuscript (which is housed at Cambridge University). The seventh-century text was written by John Climacus, an abbot of St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mt. Sinai. His treatise, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, urges Christians to pursue prayer and other spiritual disciplines in their pursuit of unity with Christ. Originally composed in Greek, this work was translated into Syriac on Mt. Sinai in the seventh century, raising intriguing historical questions about the audience of that time and place.

Finally our students will enter Mt. Sinai’s real treasure house, its library—through a manuscript that preserves the faith and experiences of our ancient spiritual fathers.

The icon was written by Elaine Hur '13 when she took Dr. Hevelone-Harper's Byzantine history course (HIS 341: Eastern Europe, Byzantium, and the Caucasus). It is based on the icon of Christ Pantocrator (Christ Ruler of All) at St. Catherine’s monastery.

Jennifer Hevelone-Harper is a professor of history at Gordon and the author of Disciples of the Desert: Monks, Laity, and Spiritual Authority in Sixth-Century Gaza (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005). The manuscript project is sponsored by the Green Scholars’ Initiative, an institution that supports teacher-mentors’ research with undergraduates.